加拿大太平洋鐵路公司

出自 MBA智库百科(https://wiki.mbalib.com/)

目錄 |

加拿大太平洋鐵路(The Canadian Pacific Railway,CPR或加太鐵路)在自治領建立之初的一個時代里,既是整個加拿大西部開拓和發展的主導性因素,又是對抗美國擴張勢力,支持麥克唐納國家政策的重要力量。它成功地用一條大鎖鏈把東西加拿大緊緊地連在一起,實現了麥克唐納國家政策的夢想,並置身於西加拿大發展的各項事業之中,為西部的開拓做出了重要的貢獻。

加拿大太平洋鐵路是加拿大的一級鐵路之一,由加拿大太平洋鐵路公司營運。其網路橫跨西部溫哥華至東部蒙特利爾,並設有跨境路線,通往美國的明尼阿波利斯、芝加哥、紐約市等大型城市。公司總部設於艾伯塔省卡爾加里。

加拿大太平洋鐵路公司修建連接全國的鐵路僅僅是開始。100多年來,加太鐵路更是擔負著政府和公眾的重托,以及管理這個龐大帝國所面對的種種挑戰,雖有曲折,但隧道的盡頭定有光明。

自從蘇格蘭移民、蒙特利爾銀行董事長喬治-史狄芬1881年創建加太鐵路公司以來,加太鐵路可謂歷盡千辛。公眾的挑剔,甚至吹毛求疵與加太鐵路的影響相比顯得無足輕重。確實如此,加太鐵路公司的第一個工程——一條橫貫加國、連接西部口岸的1900英里長鐵路,工期10年,當時被反對派譏諷為耗資巨大的荒唐行為。然而,當加太鐵路公司執行總裁唐納德-史密斯舉起鐵錘,釘下那枚著名的金質“最後道釘”的一刻,加太鐵路公司創造了兩項奇跡:工程提前五年多竣工;在經濟蕭條期內酬款1.645億加元。

那神話般的“最後道釘”似乎沖淡了加太鐵路公司征服的艱難困苦和政府的不友善關照。曾有人認為,加太鐵路公司同意修建橫跨加拿大的鐵路,並因此得到聯邦政府的2500萬加元補貼,2500萬英畝土地和710英里長鐵軌是竊取國庫。不過這些人的確低估了加太鐵路公司。加拿大俾詩省前省長曾經評論說:只有充滿冒險精神的公司才會在荒漠中建鐵路,雖然他們得到了大片的土地,但同時也承擔了巨大的風險。 19世紀末期,加太鐵路公司一度得到執政保守黨政府的優待,但好景不長。自由黨上臺後,政府開始向加太鐵路公司的競爭對手發放特許權。加太鐵路公司得以在這個資本密集型行業中取勝,並基本未傷元氣地渡過20世紀30年代的大蕭條,除得幸於其規模龐大外,主要應歸功於它傑出的經營管理。

除經營鐵路外,加太鐵路公司的章程中還包括可以經營電報、電話、碼頭,以及任何“必要和有用”的業務。在加太鐵路公司的發展史中,曾多次不得不應付來自政府的競爭。1942年,加太鐵路公司在獲得航空經營權的23年後,加拿大太平洋航空公司(Canadian Pacific Air Lines)的航班飛上了藍天。由於加拿大航空公司(Air Canada)得到了政府的支持,並獲許經營利潤豐厚的加東和國際航線,令加太航空公司的財務狀況長期處於無盈利狀態。但加太鐵路公司一直努力經營加太航空公司,直到1987年以3億加元價格將它賣給西太平洋航空公司(Pacific Western Airlines)。1981年,加太鐵路公司成立百年之時,該公司已發展為一個強大的聯合體,業務含括所有主要的運輸業、自然資源業和房地產業,年收入達126億加元,足以同時買進加拿大通用汽車、帝國石油和辛普森-西爾司這樣的大公司。與其它大型聯合公司不同的是,加太鐵路公司以商家對商家經營為主,很少直接接觸顧客。從1923年至1985年,加太鐵公司不可思議地連續62年未出現虧損。

加太鐵路公司的成功,部分原因是將日常管理交予子公司,同時提供遠期規劃和財務支持。這種分散經營的管理方式使子公司有更大的自主權和更明確的目標,為 2001年加太鐵路公司的五家子公司成功分離,獨立上市經營奠定了基礎。分離後的五家公司中,最強大的似乎仍是加太鐵路公司——老加太鐵路公司的股票每股現值70多加元,比2001年2月12日宣佈分離前升值了37%。

加拿大是一個多民族的移民國家,歷史並不悠久。然而,像跨北美大陸的加拿大太平洋鐵路(CPR)100多年來為這個年輕國家的建立和建設所做出的貢獻,這條鐵路所沉蘊涵的文化價值和歷史價值,已經成為加拿大寶貴的文化遺產。

1、CPR的緣由——建設和統一一個新的國家

1867年7月1日由英國在北美大陸東部的四個省組成聯邦,建立了一個新的國家加拿大。以後又有一些省加入。1871年位於西海岸的英屬哥倫比亞 (B.C.)省(簡稱卑詩省)被誘惑加入聯邦。其條件是在10年內建成跨大陸鐵路,將其與加拿大東部聯成一體。首任總理Sir John A. MacDonld決心“建設太平洋鐵路以統一這個國家”。這就是當時建造太平洋鐵路的緣由。

2、初期的天折——“太平洋醜聞”

太平洋鐵路項目一開始就不順利。J.A. MaCDonld的保守黨政府要求由一個私人公司來建造這條鐵路。需要撥出3000萬加元的補貼和留出5000萬英畝土地才能讓一個私人企業來完成這項工程。一個實業家和運輸業巨頭Hugh Allan是當時加拿大最富有的人。

聯邦自由黨人發現,他曾經在1872年大選中贊助過各式各樣的保守黨人共計約36萬加元,以此來確保得到這項鐵路建設合同,使其能控制這條跨大陸鐵路,以便壟斷加拿大大陸和東西海岸的交通。這個被稱為“太平洋醜聞”事件的曝光迫使該合同於1873年重新簽訂,並導致保守黨政府的倒台。

自由黨人在新一輪選舉中獲勝。這屆政府對鐵路建設的熱情就差多了,並認為可以將其作為公共工程來建設。1875年6月1日Judge Norman在Fort William附近主持了破土動工儀式,標志著加拿大太平洋鐵路建設的開始。但是,到1878年該政府換屆時只在中部省份安大略和曼尼托巴開始建設了一小段鐵路線。

3、艱難的開拓——維護統一的動力和華裔勞工的貢獻

此時,卑詩省眼看10年期限很快即至,而政治家們關於把跨大陸鐵路修到該省的承諾將無法如期兌現。於是,他們威脅說要退出聯邦。J.A. MacDonal總理1878年重新執政,在保守黨人的壓力和支持下,他不得不做一些實質性的事情,向卑詩省顯示鐵路將要修到他們省內。這屆政府與一個美國人Andrew Onderdonk簽訂了合同,開始從西海岸沿Fraser河向上游修築鐵路線。

這個美國人採用了“美國建造方法”——儘可能省錢,一味地追求利潤和進度。他的方法就是使用中國勞工。一些中國商人在卑詩省設立了勞工代理事務所,招收中國同胞去當築路工。沿著Fraser河谷陡崖的這一段線路特別艱難,615公裡長的路段用了1.5萬名勞工7年的時間才修通,其中9千人是華裔。不僅是地形、地質上的難度,而且施工方法也十分危險。

為了省錢,承包商不採用強力炸葯,而讓勞工們用便宜但很不穩定的硝化甘油來進行爆破作業。沒有確切的傷亡報告。目擊者和報紙公佈了可怕的照片,估計有700至800人死於建造這段政府合同的鐵路,大約占勞工總人數的5-9%,其中大部分是中國人。加拿大政府官員至今在每年國慶致辭中往往還會回顧華裔在這段建國曆史中的貢獻。

4、CPR公司成立——千軍易得一將難求

經董事會成員推薦,Van Horne承擔起了CPR總經理的職位。他是美國正走紅的工程界明星。CPR以1.5萬加元年薪把他從美國Milwankee道路項目上挖了過來,負責監管該跨大陸鐵路穿過草原和山脈的最艱難路段的建設。他如此高薪的2/3是隱藏在施工費用里的。他誇口其第一年任期(1882年)內將建成800公裡鐵路幹線。但天不作美,洪水迫使施工季節推遲。不過,到該施工季節末,他還是完成了673公裡幹線和177公裡支線的鋪軌任務,使太平洋鐵路似乎看到了勝利的曙光。

5、探索線路、籌集資金——網羅人才同舟共濟

CPR在這個時期還探索了比較靠南的替代線路,來穿越落基山脈,並答應給發現可行線路者5000加元的獎金。許多人為尋找新的線路作出了貢獻。其中之一Major A. B. Rogers發現了一條東部通過山脈的路徑,後來被稱為羅傑斯隘口(Rogers Pass)。他於是得到一張5000元獎金的支票。但他沒有去兌現,而是鑲在鏡框里掛在牆上。總經理Van Horne為了讓他把支票兌現,以便結帳,不得不以一塊金錶為誘餌,將這張支票從牆上換下來。

在工程初期資金流始終是一個難題。施工費用支出巨大,而從交通流量上取得回報卻很少。Van Home約請在美國Milwankee的貿易金融奇才Thomas G. Shaughnessy來幫助他解決這個問題。Thomas於1882年受雇CPR,任採購總代理,後來接替Van Horne掌管公司。在此其間他爭取到了6億加元的投資,公司得到了擴展和提升,直到第一次世界大戰爆發。

6、度過慘淡歲月——藉助政治因素和發行國際債券

在進入20世紀初的這段時期,CPR渡過了好幾個非常困難的溝坎。1883年在鋪設Calgary東段路軌時,幾乎與當地土著人發生衝突。因為鐵路要跨越他們的Gleichen自然保護區。最終公司帶著政府同意給土著人附加土地以補償鐵路占用的消息,與土著領袖一起才平息了這場危機。

在東西段鐵路將要接通前的時期,CPR面臨了她歷史上最慘淡的境遇。蘇必利爾湖的北岸、Rockies和Selkks是該鐵路使用私人資金建造部分中最艱難的區段。某些路段每公裡造價接近50萬加元。1885年初,CPR幾乎頻臨破產。公司既沒錢還債,也無錢購置新的施工材料和設備,甚至連優先股的紅利和工資都發不出來。最終有兩個人“拯救”了這條鐵路。

一個人是Louis Riel,從第一次叛亂流亡國外,1885年又回到美國領導第二次暴動。美國軍隊從東部運送到西部,全是通過加拿大接近完成的太平洋鐵路幹線,只用了幾個星期就平息了這次動亂。而1869年軍隊花了幾個月的艱難旅程,從東向西跨越北美大陸,才平息第一次叛亂。Louis Riel的所作所為,使加拿大聯邦政府明白了CPR對國家安全的重要意義,並同意確保給予CPR尚未支付的貸款。

另一個人是Revelstoke勛爵,倫敦一家著名金融公司的主管。他同意以92.5分的價格購買每一元的CPR債券,使其再次度過了財務危機。

1885年11月7日CPR創始人之一Donald Smith在卑詩省的Craigellachie砸下了“最後一顆道釘”,把太平洋沿岸與加拿大的心臟地區蒙特利爾連接了起來,標志著此跨大陸鐵路的建成。CPR負責人Van Horne說“這是一個終點,也是一個起點”。1886年6月28日第一列跨大陸列車自蒙特利爾和多倫多開往東部的默帝(Moody)港。從此以後的三年內一切都很順利,CPR又重新開始向股東分紅。鐵路有力地鞏固和增進了國家的聯合和團結,並開始了向西部的移民。鐵路把人和物資源源不斷地送到新的疆土,使沿線的城鎮和工業逐漸成長起來。

7、公司發展與戰爭考驗——國家利益高於公司利益

1889年鐵路實現了從東海岸到西海岸的全線通車。不僅如此,CPR還開拓了多種經營業務,包括房地產、跨大陸電報線路的架設和經營、自己建造蒸汽機車和車廂,以及在北美五大湖和兩大洋的海運業務。公司總經理Van Horne建議在落基山脈建立國家公園,從而CPR開始經營旅館和旅游業。CPR還因一次偶然的鑽井取水事故在阿爾德森和阿爾伯塔大草原上發現了天然氣,並用於車站和輔助建築的取暖和動力。 第二次世界大戰期間,Edwoard W. Beatty主持CPR度過了歷史上又一個困難的時期。其一是與加拿大國家鐵路公司(CNR)的商業競爭。其二是Beatty把整個公司的交通網路投入了支持戰爭的部署。在陸上,CPR運送了3.07億噸的物資,8600萬人員,其中包括15萬士兵;在海上,22艘CPR的船隻開赴前線,其中12艘被擊沉;在空中,CPR破天荒地開闢了“大西洋橋”,把轟炸機用跨洋輪渡送到英國。到1945年為止,CPR有33127名員工服務於兩次世界大戰,其中 1774人陣亡。一個私人企業仍然把國家利益置於首位。

8、近50年的演變——股份本土化和回歸鐵路主業

20世紀50年代,公司把大部分股份收回到加拿大本國的股東手中,並大大開拓了非運輸的產業部門。1962年成立了加拿大太平洋投資公司。

經過100多年的經營,到1986年加拿大太平洋公司成為加拿大第二大公司,年收入150億加元,資產177億加元,將近10萬員工。1990年CPR擴展她的鐵路網路,全部控制了美國中西部的Soo線。 1991年CPR併購了D&H鐵路公司,使其網路通達美國東北部港口城市。

2001年10月3日,加拿大太平洋公司分解為五家公司——鐵路、海運、旅館、煤炭和能源公司。其能源公司與阿爾伯塔能源公司合併為EnCana公司。鐵路公司CPR仍然經營她的主業。此時,CPR早已由客運為主轉變為貨運為主。

目前,CPR的加拿大網路包括從蒙特利爾到溫哥華的高密度幹線和許多匯入支線。她的美國部分網路延伸到中西部和東北部的工業區,可以無轉換地直達芝加哥、費城和紐約,其鐵路網路總長22536公裡。

9、歷史遺址和鐵路博物館——加拿大人心中的CPR

除了土著印第安人的歷史和早期歐洲人到北美大陸的探險外,加拿大太平洋鐵路的歷程幾乎貫穿了這個年輕國家的整個歷史。作家將其寫入自己的著作,詳細記載和描述了她的歷史事實和曲折故事,並廣為流傳。

鐵路經過的一些省份建立了鐵路博物館。在阿爾伯塔省的愛德蒙頓市,還保留了一段2.5公裡原來的鐵路線路作為歷史遺址,並改建為城市鐵路供游覽觀光。該市在老城區Strathcona複製了最初的木結構鐵路車站原型,作為一個民辦的博物館。在館里還保留著當時點煤油的信號燈和軋軋出聲的手搖電報機等文物。

1867年當加拿大剛剛建國時,人們不可能預見到100多年來這個跨北美大陸的太平洋鐵路會遭遇的全部坎坷和興旺,也不可能評估出她後來對這個國家和人們所體現的全部價值。

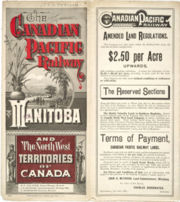

The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR; AAR reporting marks CP, CPAA, CPI), known as CP Rail between 1968 and 1996, is a Canadian Class I railway operated by Canadian Pacific Railway Limited. Its rail network stretches from Vancouver to Montreal, and also serves major cities in the United States such as Minneapolis, Chicago, and New York City. Its headquarters are in Calgary, Alberta.

The railway was originally built between eastern Canada and British Columbia between 1881 and 1885 (connecting with Ottawa Valley and Georgian Bay area lines built earlier), fulfilling a promise extended to British Columbia when it entered Confederation in 1871. It was Canada's first transcontinental railway. Now primarily a freight railway, the CPR was for decades the only practical means of long distance passenger transport in most regions of Canada, and was instrumental in the settlement and development of Western Canada. Its primary passenger services were eliminated in 1986 after being assumed by VIA Rail Canada in 1978. A beaver was chosen as the railway's logo because it is one of the national symbols of Canada and represents the hardworking character of the company. The object of both praise and damnation for over 120 years, the CPR remains an indisputable icon of Canadian nationalism.

- Before the Canadian Pacific Railway, 1871-1881

Canada's very existence depended on the successful completion of a major civil engineering project, the creation of a transcontinental railway. Creation of the Canadian Pacific Railway was a task originally undertaken for a combination of reasons by the Conservative government of prime minister Sir John A. Macdonald. British Columbia had insisted upon a national railway as a condition for joining the Confederation of Canada. The government thus agreed to build a railway linking the Pacific province to the eastern provinces within ten years of July 20, 1871. Macdonald also saw it as essential to the creation of a unified Canadian nation that would stretch across the continent. Moreover, manufacturing interests in Quebec and Ontario desired access to sources of raw materials and markets in Canada's west.

The first obstacle to its construction was economic. The logical route for a railway serving Western Canada would be to go through the American Midwest and the city of Chicago, Illinois. In addition to the obvious difficulty of building a railroad through the Canadian Rockies, an entirely Canadian route would require crossing 1,600 km (1,000 miles) of rugged terrain of the barren Canadian Shield and muskeg of Northern Ontario. To ensure this routing, the government offered huge incentives including vast grants of land in Western Canada.

In 1872, Sir John A. Macdonald and other high-ranking politicians, swayed by bribes in the so-called Pacific Scandal, granted federal contracts to Hugh Allan's "Canada Pacific Railway Company" (which was unrelated to the current company) and to the Inter-Ocean Railway Company. Because of this scandal, the Conservative party was removed from office in 1873. The new Liberal prime minister, Alexander Mackenzie, began construction of segments of the railway as a public enterprise under the supervision of the Department of Public Works. The Thunder Bay branch linking Lake Superior to Winnipeg was commenced in 1875. Progress was discouragingly slow because of the lack of public money. With Sir John A. Macdonald's return to power on October 16, 1878, a more aggressive construction policy was adopted. Macdonald confirmed that Port Moody would be the terminus of the transcontinental railway, and announced that the railway would follow the Fraser and Thompson rivers between Port Moody and Kamloops. In 1879, the federal government floated bonds in London and called for tenders to construct the 206 km (128 mile) section of the railway from Yale, British Columbia to Savona's Ferry on Kamloops Lake. The contract was awarded to Andrew Onderdonk, whose men started work on May 15, 1880. After the completion of that section, Onderdonk received contracts to build between Yale and Port Moody, and between Savona's Ferry and Eagle Pass.

On October 21, 1880, a new syndicate, unrelated to Hugh Allan's, signed a contract with the Macdonald government. They agreed to build the railway in exchange for $25,000,000 (approximately $625,000,000 in modern Canadian dollars) in credit from the Canadian government and a grant of 25,000,000 acres (100,000 km²) of land. The government transferred to the new company those sections of the railway it had constructed under government ownership. The government also defrayed surveying costs and exempted the railway from property taxes for 20 years. The Montreal-based syndicate officially comprised five men: George Stephen, James J. Hill, Duncan McIntyre, Richard B. Angus, and John Stewart Kennedy. Donald A. Smith and Norman Kittson were unofficial silent partners with a significant financial interest. On February 15, 1881, legislation confirming the contract received royal assent, and the Canadian Pacific Railway Company was formally incorporated the next day.

- Building the railway, 1881-1885

It was assumed that the railway would travel through the rich "Fertile Belt" of the North Saskatchewan River valley and cross the Rocky Mountains via the Yellowhead Pass, a route advocated by Sir Sandford Fleming based on a decade of work. However, the CPR quickly discarded this plan in favour of a more southerly route across the arid Palliser's Triangle in Saskatchewan and through Kicking Horse Pass over the Field Hill. This route was more direct and closer to the American border, making it easier for the CPR to keep American railways from encroaching on the Canadian market. However, this route also had several disadvantages.

One consequence was that the CPR would need to find a route through the Selkirk Mountains, as at the time it was not known whether a route even existed. The job of finding a pass was assigned to a surveyor named Major Albert Bowman Rogers. The CPR promised him a cheque for $5,000 and that the pass would be named in his honour. Rogers became obsessed with finding the pass that would immortalize his name. He found the pass on May 29, 1881, and true to its word, the CPR named the pass "Rogers Pass" and gave him the cheque. This however, he at first refused to cash, preferring to frame it, and saying he did not do it for the money. He later agreed to cash it with the promise of an engraved watch.

Another obstacle was that the proposed route crossed land controlled by the Blackfoot First Nation. This difficulty was overcome when the missionary Father Albert Lacombe persuaded the Blackfoot chief Crowfoot that construction of the railway was inevitable. In return for his assent, Crowfoot was famously rewarded with a lifetime pass to ride the CPR. A more lasting consequence of the choice of route was that, unlike the one proposed by Fleming, the land surrounding the railway often proved too arid for successful agriculture. The CPR may have placed too much reliance on a report from naturalist John Macoun, who had crossed the prairies at a time of very high rainfall and had reported that the area was fertile.

The greatest disadvantage of the route was in Kicking Horse Pass. In the first 6 km (3.7 miles) west of the 1,625 metre (5,330 ft) high summit, the Kicking Horse River drops 350 metres (1,150 ft). The steep drop would force the cash-strapped CPR to build a 7 km (4.5 mile) long stretch of track with a very steep 4.5% gradient once it reached the pass in 1884. This was over four times the maximum gradient recommended for railways of this era, and even modern railways rarely exceed a 2% gradient. However, this route was far more direct than one through the Yellowhead Pass, and saved hours for both passengers and freight. This section of track was the CPR's legendary Big Hill. Safety switches were installed at several points, the speed limit for descending trains was set at 10 km per hour (6 mph), and special locomotives were ordered. Despite these measures, several serious runaways still occurred. CPR officials insisted that this was a temporary expediency, but this state of affairs would last for 25 years until the completion of the Spiral Tunnels in the early 20th century.

In 1881 construction progressed at a pace too slow for the railway's officials, who in 1882 hired the renowned railway executive William Cornelius Van Horne, to oversee construction with the inducement of a generous salary and the intriguing challenge of handling such a difficult railway project. Van Horne stated that he would have 800 km (500 miles) of main line built in 1882. Floods delayed the start of the construction season, but over 672 km (417 miles) of main line, as well as various sidings and branch lines, were built that year. The Thunder Bay branch (west from Fort William) was completed in June 1882 by the Department of Railways and Canals and turned over to the company in May 1883, permitting all-Canadian lake and rail traffic from eastern Canada to Winnipeg for the first time in Canada's history. By the end of 1883, the railway had reached the Rocky Mountains, just eight km (5 miles) east of Kicking Horse Pass. The construction seasons of 1884 and 1885 would be spent in the mountains of British Columbia and on the north shore of Lake Superior.

Many thousands of navvies worked on the railway. Many were European immigrants. In British Columbia, the CPR hired workers from China, nicknamed coolies. A navvy received between $1 and $2.50 per day, but had to pay for his own food, clothing, transportation to the job site, mail, and medical care. After two and a half months of back-breaking labour, they could net as little as $16. Chinese navvies in British Columbia made only between $0.75 and $1.25 a day, not including expenses, leaving barely anything to send home. They did the most dangerous construction jobs, such as working with explosives. The families of the Chinese who were killed received no compensation, or even notification of loss of life. Many of the men who survived did not have enough money to return to their families in China. Many spent years in lonely, sad and often poor condition. Yet the Chinese were hard working and played a key role in building the western stretch of the railway; even some boys as young as 12 years old served as tea-boys.

By 1883, railway construction was progressing rapidly, but the CPR was in danger of running out of funds. In response, on January 31, 1884, the government passed the Railway Relief Bill, providing a further $22,500,000 in loans to the CPR. The bill received royal assent on March 6, 1884. Lord Strathcona drives the last spike of the Canadian Pacific Railway, at Craigellachie, 7 November 1885. Completion of the transcontinental railroad was a condition of BC's entry into Confederation.

In March 1885, the North-West Rebellion broke out in Saskatchewan. Van Horne, in Ottawa at the time, suggested to the government that the CPR could transport troops to Qu'Appelle in eleven days. Some sections of track were incomplete or had not been used before, but the trip to Winnipeg was made in nine days and the rebellion was quickly put down. Perhaps because the government was grateful for this service, they subsequently re-organized the CPR's debt and provided a further $5,000,000 loan. This money was desperately needed by the CPR. On November 7, 1885 the Last Spike was driven at Craigellachie, British Columbia, making good on the original promise. Four days earlier, the last spike of the Lake Superior section was driven in just west of Jackfish, Ontario. While the railway was completed four years after the original 1881 deadline, it was completed more than five years ahead of the new date of 1891 that Macdonald gave in 1881.

The successful construction of such a massive project, although troubled by delays and scandal, was considered an impressive feat of engineering and political will for a country with such a small population, limited capital, and difficult terrain. It was by far the longest railway ever constructed at the time. It had taken 12,000 men, 5,000 horses, and 300 dog-sled teams to build the railway.

Meanwhile, in Eastern Canada, the CPR had created a network of lines reaching from Quebec City to St. Thomas, Ontario by 1885, and had launched a fleet of Great Lakes ships to link its terminals. The CPR had effected purchases and long-term leases of several railways through an associated railway company, the Ontario and Quebec Railway (O&Q). The O&Q built a line between Perth, Ontario and Toronto (completed on May 5, 1884) to connect these acquisitions. The CPR obtained a 999-year lease on the O&Q on January 4, 1884. Later, in 1895, it acquired a minority interest in the Toronto, Hamilton and Buffalo Railway, giving it a link to New York and the northeast US.

- 1886-1900

So many cost-cutting shortcuts were taken in constructing the railway that regular transcontinental service could not start for another seven months while work was done to improve the railway's condition. However, had these shortcuts not been taken, it is conceivable that the CPR might have had to default financially, leaving the railway unfinished. The first transcontinental passenger train departed from Montreal's Dalhousie Station, located at Berri Street and Notre Dame Street on June 28, 1886 at 8:00 p.m. and arrived at Port Moody on July 4, 1886 at noon. This train consisted of two baggage cars, a mail car, one second-class coach, two immigrant sleepers, two first-class coaches, two sleeping cars, and a diner.

By that time, however, the CPR had decided to move its western terminus from Port Moody to Gastown that was renamed "Vancouver" later that year. The first official train destined for Vancouver arrived on May 23, 1887, although the line had already been in use for three months. The CPR quickly became profitable, and all loans from the Federal government were repaid years ahead of time.

In 1888, a branch line was opened between Sudbury and Sault Ste. Marie where the CPR connected with the American railway system and its own steamships. That same year, work was started on a line from London, Ontario to the American border at Windsor, Ontario. That line opened on June 12, 1890. The CPR also acquired several small lines east of Montreal; it also leased the New Brunswick Railway for 999 years, and built the International Railway of Maine, connecting Montreal with Saint John, New Brunswick in 1889. The connection with Saint John on the Atlantic coast made the CPR the first truly transcontinental railway company and permitted trans-Atlantic cargo and passenger services to continue year-round when sea ice in the Gulf of St. Lawrence closed the port of Montreal during the winter months.

By 1896, competition with the Great Northern Railway for traffic in southern British Columbia forced the CPR to construct a second line across the province, south of the original line. Van Horne, now president of the CPR, asked for government aid, and the government agreed to provide around $3.6 million to construct a railway from Lethbridge, Alberta through Crowsnest Pass to the south shore of Kootenay Lake, in exchange for the CPR agreeing to reduce freight rates in perpetuity for key commodities shipped in Western Canada. The controversial Crowsnest Pass Agreement effectively locked the eastbound rate on grain products and westbound rates on certain "settlers' effects" at the 1897 level. Although temporarily suspended during World War I, it was not until 1983 that the "Crow Rate" was permanently replaced by the Western Grain Transportation Act which allowed for the gradual increase of grain shipping prices. The Crowsnest Pass line opened on June 18, 1899.

- The CPR and The Colonization of Canada

Practically speaking, the CPR had built a railway that operated mostly in the wilderness. The usefulness of the Prairies was questionable in the minds of many. The thinking prevailed that the Prairies had great potential. Under the initial contract with the Canadian Government to build the railway, the CPR was granted 25,000,000 acres (100,000 km²). Proving already to be a very resourceful organization, Canadian Pacific began an intense campaign to bring immigrants to Canada.

CP agents operated in many overseas locations. Immigrants were often sold a package that included passage on a CP ship, travel on a CP train, and land that was purchased from the CP railway. Land was sold at $2.50 an acre and up. Immigrants paid very little for a seven day journey to the West. They rode in Colonist cars that had sleeping facilities and a small kitchen at one end of the car. Children were not allowed off the train as they often would wander off and be left behind. The owners of the CPR knew that not only were they creating a nation, but also a source of economy for their company.

- 1901-1928

During the first decade of the twentieth century, the CPR continued to build more lines. In 1908 the CPR opened a line connecting Toronto with Sudbury. Previously, westbound traffic originating in Southern Ontario took a circuitous route through Eastern Ontario.

Several operational improvements were also made to the railway in Western Canada. In 1909 the CPR completed two significant engineering accomplishments. The most significant was the replacement of the Big Hill, which had become a major bottleneck in the CPR's main line, with the Spiral Tunnels, reducing the grade to 2.2% from 4.5%. The Spiral Tunnels opened in August. On November 3, 1909, the Lethbridge Viaduct over the Oldman River valley at Lethbridge, Alberta was opened. It is 1,624 metres (5,327 ft) long and, at its maximum, 96 metres (314 ft) high, making it the longest railway bridge in Canada. In 1916 the CPR replaced its line through Rogers Pass, which was prone to avalanches, with the Connaught Tunnel, an eight km (5 mile) long tunnel under Mount Macdonald that was, at the time of its opening, the longest railway tunnel in the Western hemisphere.

The CPR acquired several smaller railways via long-term leases in 1912. On January 3, 1912, the CPR acquired the Dominion Atlantic Railway, a railway that ran in western Nova Scotia. This acquisition gave the CPR a connection to Halifax, a significant port on the Atlantic Ocean. The Dominion Atlantic was isolated from the rest of the CPR network and used the CNR to facilitate interchange; the DAR also operated ferry services across the Bay of Fundy for passengers and cargo (but not rail cars) from the port of Digby, Nova Scotia to the CPR at Saint John, New Brunswick. DAR steamships also provided connections for passengers and cargo between Yarmouth, Boston and New York. On July 1, 1912, the CPR acquired the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway, a railway on Vancouver Island that also connected to the CPR by car ferry. The CPR also acquired the Quebec Central Railway on December 14, 1912.

During the late 19th century, the railway undertook an ambitious program of hotel construction, building the Chateau Frontenac in Quebec City, the Royal York Hotel in Toronto, the Banff Springs Hotel, and several other major Canadian landmarks. By then, the CPR had competition from three other transcontinental lines, all of them money-losers. In 1919, these lines were consolidated, along with the track of the old Intercolonial Railway and its spurs, into the government-owned Canadian National Railways.

When World War I broke out in 1914, the CPR devoted resources to the war effort, and managed to stay profitable while its competitors struggled to remain solvent. After the war, the Federal government created Canadian National Railways (CNR, later CN) out of several bankrupt railways that fell into government hands during and after the war. CNR would become the main competitor to the CPR in Canada.

- The Great Depression and World War II, 1929-1945

The Great Depression, which lasted from 1929 until 1939, hit many companies heavily. While the CPR was affected, it was not affected to the extent of its rival CNR because it, unlike the CNR, was debt-free. The CPR scaled back on some of its passenger and freight services, and stopped issuing dividends to its shareholders after 1932.

One highlight of the 1930s, both for the railway and for Canada, was the visit of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth to Canada in 1939, the first time that the reigning monarch had visited the country. The CPR and the CNR shared the honours of pulling the royal train across the country, with the CPR undertaking the westbound journey from Quebec City to Vancouver.

Later that year, World War II began. As it had done in World War I, the CPR devoted much of its resources to the war effort. It retooled its Angus Shops in Montreal to produce Valentine tanks, and transported troops and resources across the country. As well, 22 of the CPR's ships went to war, 12 of which were sunk.

- 1946-1978

After World War II, the transportation industry in Canada changed. Where railways had previously provided almost universal freight and passenger services, cars, trucks, and airplanes started to take traffic away from railways. This naturally helped the CPR's air and trucking operations, and the railway's freight operations continued to thrive hauling resource traffic and bulk commodities. However, passenger trains quickly became unprofitable.

During the 1950s, the railway introduced new innovations in passenger service, and in 1955 introduced The Canadian, a new luxury transcontinental train. However, starting in the 1960s the company started to pull out of passenger services, ending services on many of its branch lines. It also discontinued its transcontinental train The Dominion in 1966, and in 1970 unsuccessfully applied to discontinue The Canadian. For the next eight years, it continued to apply to discontinue the service, and service on The Canadian declined markedly. On October 29, 1978, CP Rail transferred its passenger services to VIA Rail, a new federal Crown corporation that is responsible for managing all intercity passenger service formerly handled by both CP Rail and CN. VIA eventually took almost all of its passenger trains, including The Canadian, off CP's lines.

In 1968, as part of a corporate re-organization, each of the CPR's major operations, including its rail operations, were organized as separate subsidiaries. The name of the railway was changed to CP Rail, and the parent company changed its name to Canadian Pacific Limited in 1971. Its express, telecommunications, hotel and real estate holdings were spun off, and ownership of all of the companies transferred to Canadian Pacific Investments. The company discarded its beaver logo, adopting the new Multimark logo that could be used for each of its operations.

- 1979-present

In 1984 CP Rail commenced construction of the Mount Macdonald Tunnel to augment the Connaught Tunnel under the Selkirk Mountains. The first revenue train passed through the tunnel in 1988. At 14.7 km (9 miles), it is the longest tunnel in the Americas.

During the 1980s, the Soo Line, in which CP Rail still owned a controlling interest, underwent several changes. It acquired the Minneapolis, Northfield and Southern Railway in 1982. Then on February 21, 1985, the Soo Line obtained a controlling interest in the Milwaukee Road, merging it into its system on January 1, 1986. Also in 1980 Canadian Pacific bought out the controlling interests of the Toronto, Hamilton and Buffalo Railway (TH&B) from Conrail and molded it into the Canadian Pacific System, dissolving the TH&B's name from the books in 1985. In 1987 most of CPR's trackage in the Great Lakes region, including much of the original Soo Line, were spun off into a new railway, the Wisconsin Central, which was subsequently purchased by CN. Influenced by the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement of 1989 which liberalized trade between the two nations, the CPR's expansion continued during the early 1990s: CP Rail gained full control of the Soo Line in 1990, and bought the Delaware and Hudson Railway in 1991. These two acquisitions gave CP Rail routes to the major American cities of Chicago (via the Soo Line) and New York City (via the D&H).

During the next few years CP Rail downsized its route, and several Canadian branch lines were either sold to short lines or abandoned. This included all of its lines east of Montreal, with the routes operating across Maine and New Brunswick to the port of Saint John (operating as the Canadian Atlantic Railway) being sold or abandoned, severing CPR's transcontinental status (in Canada); the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in the late 1950s, coupled with subsidized icebreaking services, made Saint John surplus to CPR's requirements. During the 1990s, both CP Rail and CN attempted unsuccessfully to buy out the eastern assets of the other, so as to permit further rationalization. As well, it closed divisional and regional offices, drastically reduced white collar staff, and consolidated its Canadian traffic control system in Calgary, AB.

Finally, in 1996, reflecting the increased importance of western traffic to the railway, CP Rail moved its head office to Calgary from Montreal and changed its name back to Canadian Pacific Railway. A new subsidiary company, the St. Lawrence and Hudson Railway, was created to operate its money-losing lines in eastern North America, covering Quebec, Southern and Eastern Ontario, trackage rights to Chicago, Illinois, as well as the Delaware and Hudson Railway in the U.S. Northeast. However, the new subsidiary, threatened with being sold off and free to innovate, quickly spun off losing track to short lines, instituted scheduled freight service, and produced an unexpected turn-around in profitability. After only four years, CPR revised its opinion and the StL&H formally reamalgamated with its parent on January 1, 2001.

In 2001, the CPR's parent company, Canadian Pacific Limited, spun off its five subsidiaries, including the CPR, into independent companies. Canadian Pacific Railway formally (but, not legally) shortened it's name to Canadian Pacific in early 2007, dropping the word "railway" in order to reflect more operational flexibility. Shortly after the name revision, Canadian Pacific announced that it had committed to becoming a major sponsor and logistics provider to the 2010 Olympic Winter Games in Vancouver, British Columbia.